We may contemplate our future with dread and uncertainty or with joy and anticipation. But sometimes we see no future.

I came to Ann Patchett’s “What Now?” in the meandering vein of “Things I learned Enroute to Looking Up Other Things” columns. I read Dutch House, which convinced me that Patchett was a good writer. So I read Tom Lake which convinced me that Patchett was a very, very good writer. Not that Tom Lake was somehow much better than Dutch House, it’s just that of the very small set of people who can write one very good novel, only a tiny percentage can write two very good novels. Which led, when out of audio books on Libby, to getting the exactly one “Available Now” listing by Patchett — “What Now?”

It turned out to be (via a graduation speech) an exploration of my favorite topic in philosophy — transformative choice (albeit without any hint of academic philosophy). Patchett looks at the big decisions in our life: decisions about college, career, and family — decisions that shape who we become and what our life looks like. The speech is about how to take the “what now?” question that plagued her throughout her early life and change it into something positive.

She starts, appropriately given her audience of Sarah Lawrence graduates, with the first big transformative decision most of us make: where to go to college.

“The first time I reached that particular impasse in my life I was in High School and the burning question concerning my future was where I was going to college. Every day I stood at the window watching for the mailman and as soon as he had driven safely away, for some reason I thought it was important to conceal my eagerness from the mailman, I would dart out to the box and search for the documents that would determine my fate…but not a single envelope bore my name.

It seemed in those days that the world only had one question for me and it was not “how are you feeling?” or “what is the state of your soul?” or “what is it you want from life?”. No, the only thing anyone asked me back then was “where are you going to college?”.

It’s a question natural, inevitable, and deeply anxiety-inducing. Because in the great college-admissions crap shoot, even the best students don’t really have an answer. And say what you will, every ambitious HS student is convinced that where they go to college will ultimately determine the nature and shape of their life.

Every prospective student hates the “what now” question. Hates the uncertainty, the possibility of failure, the pain of it all. “What now?” embodies all the challenges we have finding a path, building an identity, becoming who we want to be and sticking with it.

Asking “what now?” sucks and, however well intentioned, it sucks the life from those questioned.

But for the students getting their Sarah Lawrence diplomas that day, the next part of Ann Patchett’s “what now?” was probably visible almost before the words were out of her mouth. Because while most of us can settle pretty comfortably into college life, when that four-year sabbatical comes to an end, the “what now?” question returns with even greater force. Unless you are going off to get a law or medical degree, the next choice you make really is unknown territory.

For Patchett, who never wanted anything but to be a writer, the way forward was particularly unclear. You can’t just send out a bunch of resumes to get started. She went home and was a line cook in a restaurant. She thought about writing a lot, but she didn’t do much. Because working is…work. It’s hard, it keeps you busy, and at the end of the day, most of those who do it are too tired to write much. She got fired and became a waitress.

You never know, listening to this kind of capsule biography, exactly what to make of that. I worked summers during college cleaning restrooms 2nd shift in a GE Plant. That doesn’t mean I was ever in danger of becoming a maintenance man for life. And while George Orwell was homeless for Down & Out in Paris and London, he was summer-break homeless until his real job started. Of course, Patchett wanted to be a writer, but everybody wants to be a writer. Still, I doubt Patchett was in any danger of being a waitress by profession. Nor do I think it matters much.

In one of the best parts of the speech, Patchett describes some of what she learned being a waitress.

“In a world that is flooded with children’s leadership camps and grown-up leadership seminars and best-selling books on leadership, I count myself as fortunate to have been taught a thing or two about following. Like leading, it is a skill. And unlike leading, it is one that you will actually get to use on a daily basis. It is senseless to think that at every minute of our lives we will all be the Team Captain, the General, the CEO…Yet this is all what we’re being prepared for…No matter how many great ideas you might have about salad bars…waitressing is not a leadership position.

You’re busy, so you ask somebody else to bring the water to Table 4. Somebody else is busy, and so you clear the dirty plates from Table 12…You learn to be helpful. And you learn to ask for help…Being successful and certainly being happy, comes from honing your skills in working with other people…It wasn’t until I found myself relying on my fellow waitress, Regina, to heat up my fudge sauce for me that I knew enough to grateful, not only for the help she was giving me, but for the education [Catholic school] that had prepared me to accept it”

Patchett threads the needle. She doesn’t con you into thinking she’d be happy if she’d stayed a waitress. But you can tell that in many ways she liked it, and she learned a lot. More than I learned cleaning toilets anyway. It’s the kind of thing most Sarah Lawrence graduates probably wouldn’t ever really believe, but coming from and about Patchett it carries conviction.

Patchett charts her own course to being a novelist (or at least the sort of novelist she is) less through Sarah Lawrence and the Iowa Workshop and more through Catholic school, babysitting, a chance encounter with a Hare Krishna (a story she clearly loves to tell and isn’t at all what you think), and, yes, waitressing.

“For the most part wisdom comes in chips rather than blocks. You have to be willing to gather them constantly, and from sources you never imagined to be probable. No one chip gives you the answer for everything. No one chip stays in the same place throughout your entire life. The secret is to keep adding voices, adding ideas, and moving things around as you put together your life. If you’re lucky, putting together your life is a process that will last through every single day you’re alive.”

Eventually, she gives up on restaurant work and applies to and is accepted at the Iowa MFA program (I have no idea if the Iowa Program teaches anybody anything — Patchett elsewhere implies they don’t — but they sure can recognize talent). Giving her a whole new answer to the “what now?” question that had to feel a lot better than “waitressing”. But, of course, even the Iowa MFA program must end and when Patchett reached that end, she had to face the “what now?” question yet again.

It’s a question, Patchett suggests, will never stop. More importantly, it’s a question that should never stop. Because what now isn’t just the question the world is constantly annoying us with, it’s the question that we should be asking ourselves. I’d bet that 99% of those Sarah Lawrence grads hated asking themselves and being asked “what now?” — I know I did when I was their age and in their position. Yet “what now?” is a question we really should be asking ourselves.

“What now is not just a panic-stricken question tossed into a dark unknown. What now can also be our joy. It is a declaration of possibility, of promise, of chance. It acknowledges that our future is open, that we may well do more than anyone expected of us, that at every point in our development we are still striving to grow.”

It may seem easy, if you’re Ann Patchett, to be excited about what’s next. She’s had an enormously successful life — the kind of life that breeds the confidence to think of what’s next with anticipation. But if anyone has earned the right to preach being excited about asking “what now”, it is the successful novelist. It’s as gutsy a choice of profession as you can make. Besides, how many newly-minted Sarah Lawrence graduates don’t have plenty to look forward to? And they are young.

Youth is a great advantage, though when it comes to asking “what now?” youth is not in the peculiar position it tends to imagine for itself. One of the greatest myths and most insidious ideas that our culture gives us is the idea that once we are adults, we are done becoming who we are. This is manifestly untrue on any practical observation and profoundly mistaken from the perspective of cognitive science.

Our brains are adaptive learning machines. Every experience changes us at least a little. The one thing we cannot do — no matter how little or much we do, no matter how great or small our effort — is stay the same. And because experience changes who we are, when we make big picture decisions we are necessarily choosing the kind of person we are trying to become. We are answering the “what now?” question and we never quite stop answering it until we’re so close to death that the only thing left to do is say good-bye.

It never stops being asked, even if society is too stupid, blind or intimidated to voice the question. Life voices the question, and we have no choice but to answer. Because even doing nothing or doing exactly what we’ve been doing is a kind of answer. And if you’re trying to answer that question more explicitly, Patchett is surely right that it’s better to approach it with hope and excitement than fear and anxiety.

That’s easier said than done and not just because we are mostly not as successful in our lives as Patchett. It is tempting to credit Patchett’s openness to change to her past success and let ourselves off the hook for our fear and uncertainty. “Of course, it’s easier for her.” But it’s just as likely that Patchett’s particular kind of success comes from her willingness to embrace that question. Whichever is the cart and which the horse, success is surely no guarantor of an openness to change. Many of the most successful people are breathtakingly afraid to ask “what now” precisely because they have the most to lose.

Which brings me to the third and final sense of “what now”. The sense that Patchett — talking to college graduates — doesn’t bother with. Because although new Sarah Lawrence graduates have, like everyone, their share of pain and trouble, most of them haven’t ever suffered a major failure in a life project. Most have never had a life project.

When you’re in school, everything is about potential. Nobody expects you to achieve anything. All you’re really working on is building potential.

But once you stop being a student, you’re expected to do something. And the things you invest yourself in become, far more than your potential, your identity. As an adult, to describe yourself as a mathematician is not to suggest that you are good at math, it is to say that you DO mathematics.

The biggest and most important things we invest ourselves in are the ways we use that potential — they are our life projects. For most of us, the biggest life projects are career and family. But that needn’t be the case. Your life project may be a hobby or an idea (a hobby-horse). Your life project(s) may be creating art, wielding political power, raising great kids, or building a business.

Not everything we do is a life project. My life project isn’t hiking or gardening or even dining out or reading books — though an impartial observer might question those last assertions. I do all those things, and I do some of them a LOT. But I don’t invest my identity in them. I do not think of myself as a diner. Nor is it really possible to fail or succeed at such things. You can be a good or bad reader, and I suppose one can even be a good or bad diner — but one is not a successful or failed diner.

There is a strain in philosophical and religious thinking that glorifies withdrawal from the world. Socrates treating life as a kind of preparation for death. This is not the way most of us see things. We expect people to be engaged with the world. We admire people with significant life projects. People who invest themselves in the world. Monasticism is no longer an ideal.

But there was a reason that philosophers and theologians distrusted this investment in life. It’s a risk. Everything in the world is contingent. Success or failure is always contingent on others. And others, as we are all bound to discover, cannot be relied on. Kids fail or, far worse, they may die. Our work and career can vanish or be utterly rejected by the culture we live in. A marriage can fall apart. A family can dissolve. The risk isn’t just to your project, it’s to, and I mean this literally, your self. Because life projects become and — given what they are — must become — a part of your identity. If you fail at them, you lose a part of who you are.

And the bigger and more central a project is to your identity, the more crippling its failure can become. At its most devastating, the failure of a core life project can end any real hope of a useful life.

We don’t like to think of it this way. Our culture tends to relentlessly positive about life possibilities. No matter the situation, we like to think life has worth. Our taboo against suicide is one of the many cases where we have preserved Christian morals in our folk ethics while abandoning any pretense of Christian thought. Many other cultures are not similarly encumbered. Pre-Christian Rome accepted suicide as a reasonable alternative when one’s core life projects have been annihilated. Japan’s samurai code accepted suicide as a possible response to any significant failure of identity. Surely that, at least, flies in the face of a great deal of experience suggesting that people can recover and lead valuable and valued lives even after crushing blows to their core life projects. Yet it’s not true that everyone recovers — especially when the blows come later in life.

It is in these cases where we have suffered a crushing blow to a core life project that the third sense of “what now?” emerges. We cry out “what now?” in despair and hopelessness. Asking the question in a world where nothing seems possible and where grief or failure have stripped us of anything to value.

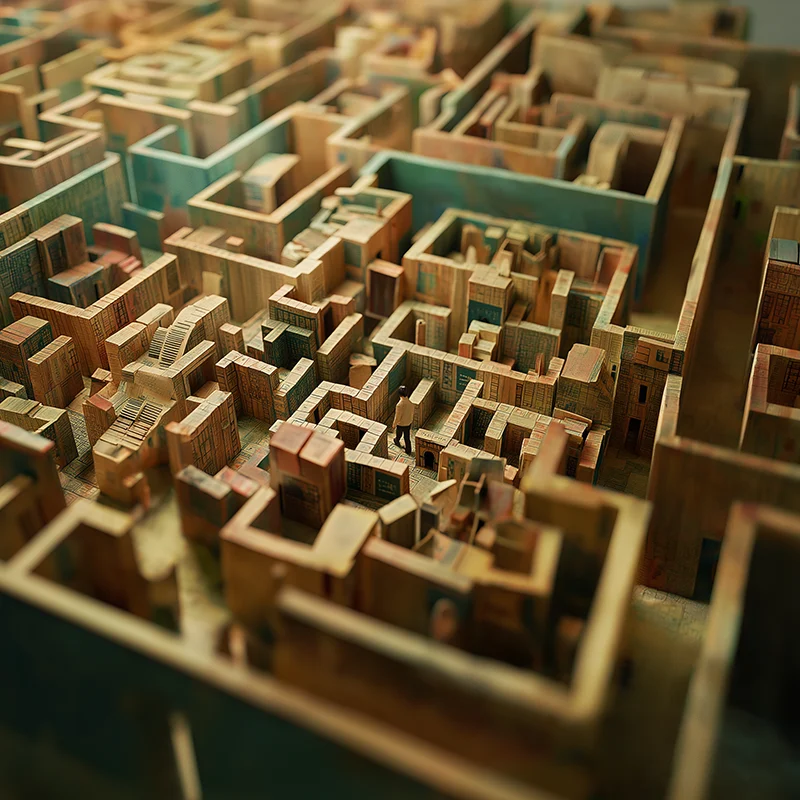

When we cry out “what now?” in this way, we are not in the situation of the High School senior nervously afraid of failure. And we are certainly not in Patchett’s vein of anticipation and excitement. We are at the end of the trail, facing a blank wall, night is setting in, and the way home is irreparably blocked. Our life is at a dead-end — not because there is no path forward — but because there is no longer a reason to continue onward.

In this “what now?” the question has been transmuted in a way curiously similar to Patchett’s. For when Patchett asks what now, her question is less about action and more about value. The High School seniors or Sarah Lawrence grads know what they want; they lack the way forward. They want to go to a good college. They want a good job. They want to write. They are afraid, confused, and indecisive not for lack of values, but for lack of clarity. In Patchett’s case, though, she CAN do almost anything. Her problem isn’t lack of clarity, it’s deciding what to value, what to try, who to become. No wonder she’s more excited than the High School senior! Her problem is a better one to have.

Except when it isn’t.

Because like Patchett’s, the despairing “what now?” isn’t about a path forward or about options. The people who utter it after the death of a beloved child, the crushing of their one career dream after many years of successful pursuit, or in the death of a spouse of many, many years do not lack a path forward. They could often continue to live almost exactly as they have been living. What they lack is a reason to value any of those paths and actions.

There is no human problem harder to overcome than lacking values. It is the problem of the deepest depressions and the most devastating of life blows. Though I have written much (and felt much) recently about grief, that grief — however intense — is not, for me, the end of value. The death of a parent is not the end of one’s life projects. You are their life project; they are not yours.

It would be easy to conflate grief with the terrible loss we experience when our most core life projects fail. It’s a failure that may well be accompanied by terrible grief. But grief itself can be felt without any change in one’s life projects. We grieve at the loss of a parent, of a close friend, or a loved pet. And, yes, the grief we feel may trigger that sense of everything losing value. I have sometimes felt that loss in brief moments these past weeks when the most desolate “what now?” seems like a genuine question.

Yet even these intense griefs need not bring us so low, and if they do, our balance is usually quickly and gratefully restored as both the demands and attractions of life distract and heal us.

But the loss of identity, of self, that comes with a crushing failure of something that WAS our life may leave us with no sense of how we can recover. We may well feel that there is no self left to recover.

I have never been in that place. Most of us have not. Most of us don’t invest in one thing so fully that failure — even epic failure — leaves us stranded without self or value. Some of us are even luckier and never experience failure in the one great thing that defines them. Ann Patchett is likely such a one. That may be the best life any of us can manage. For if the first sense of “what now?” is everyone at some times in their life, and the second is a sense that only the best of us can frequently manage, the third is for the unlucky few who build a life on one thing only to see it blasted by the contingencies of the world.

The person that emerges from that desolation is nothing like the person who endured it. We may indeed think of them as being, for better or worse, another person entirely. Yet for all of that, they are the luckiest of those least lucky few — they have found some answer to the final sense of “what now?” that is not death.