Ted Chiang’s Exhalation is a classic Sci-Fi short story. Brilliant, evocative, thought-provoking, deeply humanistic and inspirational. It tells of the end of days for race of mechanical men undone by the remorseless laws of the universe. It’s the title story of his 2019 collection, and while that collection is chock-full of great stories (especially the remarkable opening story), Exhalation stands out. It’s that good. And while I’ve read Exhalation multiple times, a recent re-reading cast a whole new set of shadows on the story — deepening, at least for me, its meanings.

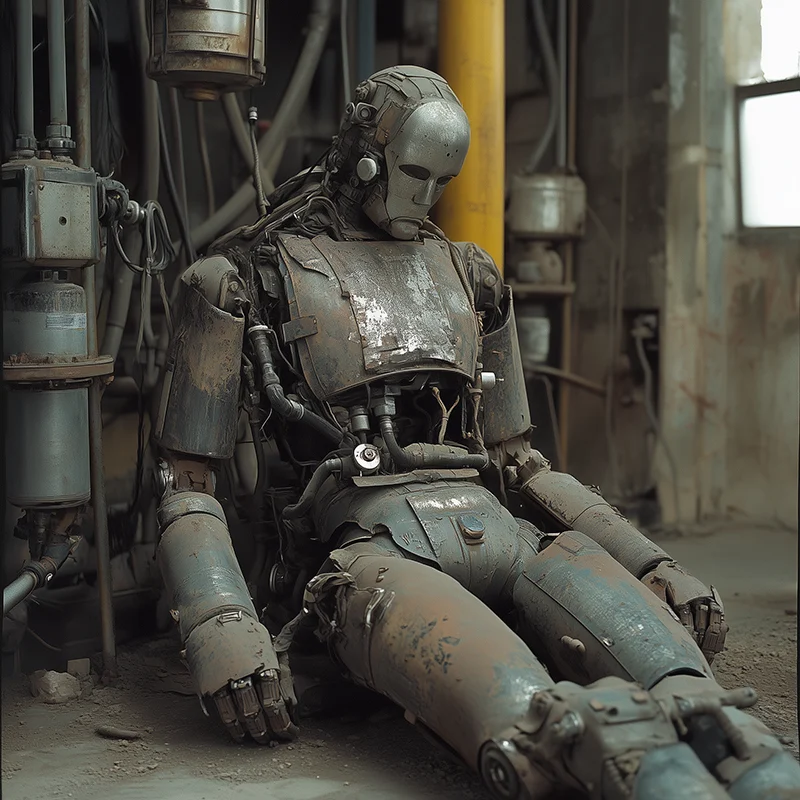

Exhalation’s mechanical men live in a giant argon-filled bubble and compressed argon is the air that keeps them alive and lets them function. They are permanent scuba-divers inside a bubble-world. Within their chests are two tanks of compressed argon which power them. When the tanks get low, they go to a centralized facility and swap them out while exchanging news and gossip.

There is trouble lurking here, though it becomes visible in the most innocuous form. The town crier doing a ritual presentation is slightly off, finishing a little too late. And not just one town crier, but many. The hero of Exhalation has a troubling suspicion. If the mechanical clocks are not going faster (and evidence strongly suggests they are not), then perhaps the Argonauts are going slower. A scientist by nature, he decides to attempt a remarkable experiment — a dissection of his own brain.

In one of the most remarkable scenes of science fiction ever put on paper, he brings a number of spare bottles of argon, creates a mirror setup that lets him see the back of his head, and then uses a pair of delicate, precise mechanical hands to open up the back of his skull and slowly take apart the machinery in his head.

To get access to the central components, this means he must rapidly disconnect (and then reconnect using longer tubes) an array of air hoses letting him move parts of his brain outside his skull. Imagine one of those exploded visualizations with the parts floating out in space and you will have the idea. After many hours he gets to the central processing unit and, with a microscopic lens, is able to see that it is an incredibly complex array of tiny golden leaves constantly adjusting their positions via a continuous flow of air. It is a neural net built from the unceasing flow of argon gas.

Without that steady flow, they die. Even a brief cessation destroys the dynamic state of their minds — erasing them in the process. Yet despite this fragility, they are essentially immortal. They can be damaged or destroyed. Without new tanks of argon, they will perish. But they do not age and they show no real evidence of wearing down. So in piercing the veil of their anatomy, not only does the hero discover the cause of the misaligned criers he discovers their doom.

It is death by thermodynamics:

“But if our thoughts were purely patterns of air rather than the movement of toothed gears, the problem was much more serious, for what could cause the air flowing through every person’s brain to move less rapidly? It could not be a decrease in the pressure from our filling stations’ dispensers; the air pressure in our lungs is so high that it must be stepped down by a series of regulators before reaching our brains. The diminution in force, I saw, must arise from the opposite direction: the pressure of our surrounding atmosphere was increasing.

How could this be? As soon as the question formed, the only possible answer became apparent: our sky must not be infinite in height. Somewhere above the limits of our vision, the chromium walls surrounding our world must curve inward to form a dome; our universe is a sealed chamber rather than an open well. And air is gradually accumulating within that chamber, until it equals the pressure in the reservoir below.

This is why…I said that air is not the source of life. Air cannot be created or destroyed. The total amount of air in the universe remains constant, and if air were all we needed to live, we would never die. But in truth, the source of life is a difference in air pressure…when the pressure everywhere in the universe is all the same, all air will be motionless and useless.

We are not really consuming air at all…all I am doing is converting air at high pressure to air at low.”

He has discovered not only the death of universe, but death. Death is inevitable because it is baked into the physical laws of the universe. Not our universe’s cold death in an unimaginable future, but personal, civilizational and species death all rolled into a single trainwreck visible in the converging rails of the not-too-distant horizon.

As word spreads about his anatomical discoveries and their implications, reactions vary from panic to determination to resignation. Our hero does not panic, nor does he believe in the discovery of some perpetual motion machine that can save them. Yet his resignation is tinged with a different kind of existential hope. He chronicles his civilization for those who might eventually find their way into his universe.

It is a beautiful story. Like all of Chiang’s best work, Exhalation is an imaginative jewel box with a humanist key. And in my latest reading, that key unlocked a new, a bitter set of revelations all bound up in the nature of the death Chiang imagines.

“So that our thoughts may continue as long as possible, anatomists…are designing replacements for our cerebral regulators, capable of gradually increasing the air pressure within our brains and keeping it just higher than the surrounding atmospheric pressure. Once these are installed, our thoughts will continue at roughly the same speed even as the air thickens around us. But this does not mean that life will continue unchanged. Eventually the pressure differential will fall to such a level that limbs will weaken and our movements will grow sluggish….”

As I write this, my mother is dying of ALS. She is old, of course, and whether from age or ill luck the progression of the ALS has been devastatingly fast. Each Monday she is weaker. Her speech more slurred. Her legs failing. Her hands tremblier. I see her every day, but even that does not slow the perceived speed of her descent. It is a fall in not quite slow-motion. And in that fall, I see that she is more afraid of immobility and loss of language on the way down than of death at the end.

For all the wonders of our technology, how is she supposed to communicate? Her hands are too shaky for even the largest buttons now. Her eyes too poor for most screens. Her words recognizable only to those who know her best and listen to her most. Four months ago, she walked everywhere, talked with authority, wrote constantly. Now that is all vanishing. It is a terrifying way to die, though it has, in her case, the advantage of speed.

But once again I see her fate in Exhalation.

“At some point our limbs will cease moving altogether. I cannot be certain of the precise sequence of events near the end, but I imagine a scenario in which our thoughts will continue to operate, so that we remain conscious but frozen, immobile as statues.”

A tragic fate for a metal man, but how much worse to make a statue of flesh-and-blood with only thought in motion?

For Chiang’s Argonauts, the possibility of communication until the end still exists even though it will speed their fate.

“Perhaps we’ll be able to speak for a while longer…but our every utterance will reduce the amount of air left and bring us closer to the moment when our thoughts cease altogether. Will it be preferable to remain mute to prolong our ability to think, or to talk until the very end? I don’t know.”

But I think the choice is clear. At least for my mother, and I think for most of us, silence is not an option. We cannot choose to sit quietly in thought as we march toward death. My mother struggles for every word, but as the end nears, each word understood by others is worth an hour to her.

Chiang’s narrator believes they too will struggle on to the very end.

“Perhaps a few of us…will be able to connect our cerebral regulators directly to the dispensers in the filling stations…replacing our lungs with the mighty lung of the world. If so, those few will be able to remain conscious right up to the final moments before all pressure is equalized. The last bit of air pressure left in our universe will be expended driving a person’s conscious thought.”

And perhaps that’s true. Certainly, for those whose dying is a not proceeded by the death of their mind, the will to communicate and the power of thought persist right up until the last ragged breaths are torn from the body. Our last calories are burned in the brain.

This is desolate fate for an entire people, an entire world. Yet Chiang finds, even in this terrible end, a path forward. The Argonauts will die together, their only hope that some chance will bring others to read of their fate and civilization.

“Which is why I have written this account. You, I hope, are one of those explorers. You, I hope, found these sheets of copper and deciphered the words engraved on their surfaces…through the collaborative action of your imaginations, my entire civilization lives again…”

But if an Argonaut can hope to live in the imagination of some future explorers, we are not so desolate of hope. We have a more tangible, biological destiny. My mother hopes to see me again. I do not share that belief, though it would be a harder heart than mine that would say so in these final days. Like the Argonauts, we would like to be remembered, and I can, at least, promise her that. But even those of us who have no place on the ofrenda persist. We have left our mark on the minds, the characters and perhaps even the genes of others. We do not vanish without a trace.

The last words of an Argonaut are proof that they, too, will not sail quietly into the night.

“Though I am long dead as you read this, explorer, I offer you a valediction. Contemplate the marvel that is existence and rejoice that you are able to do so. I feel I have the right to tell you this because, as I am inscribing these words, I am doing the same.”

My mother can no longer put finger to key. Her slurred words have gone completely silent. But she, too, loved this story. And we both found inspiration in these final words, though she with far more right.