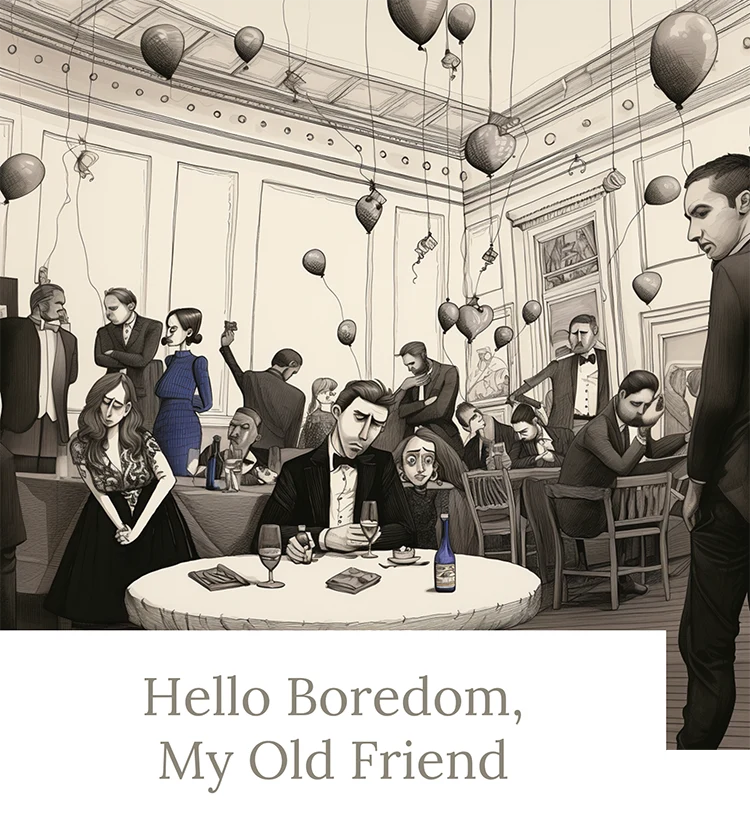

The one ill no one would expect in our society is boredom. Our lives might not be good, but surely they are too frenetic and occupied to make boredom a problem. Yet people are bored and the evidence is everywhere – not least in the immense value we place on entertainment and distraction. What boredom is telling us and why we should listen.

The decisions we make about what to be and who to become are the biggest and, especially in our society, some of the hardest choices we have as decision-makers. Transformative decisions have always been central to a life, but our culture makes them especially challenging. It offers almost unlimited choice, extraordinary freedom and tremendous resources. It also provides constant distraction, terrible reinforcement and feedback, and virtually no guidance or way to think about these choices except in the most banal and materialistic terms.

Yet with all that choice, with so much to acquire, and so many things to try, the one problem you wouldn’t expect in Western society is…boredom. It seems impossible that anyone could be bored in our dazzling and frenetic culture. But bored we often are, and the signs and evidence of boredom are everywhere. Nor is our boredom a product of social media or screen addiction – though our infatuation with both is an obvious symptom.

Writing Humboldt’s Gift way back in the ’70s, Saul Bellow described boredom as the central problem of modern society. In the early 2000’s David Foster Wallace treated boredom similarly in The Pale King. But while great novelists are always the best diagnosticians of their current culture, we need not rely on them to see how large the problem of boredom looms for us.

We can follow the money.

Progressives, who, like generals, are always fighting the last war, still think of the wealthy as corporate CEOs. CEOs make plenty, but the most spectacularly remunerated and respected people in our society are entertainers. How many corporate CEOs make what Lebron James makes? Or Oprah? Or Jim Rome? Or Kim Kardashian? Or Kanye West? How many kids wear Chris Hohn jerseys or follow Bob Swan on Instagram? A mediocre fifth man on the average NBA team makes more money than all but a tiny number of CEOs. Tony Romo, a retired quarterback, is paid 20 million dollars a year to be a commentator on 16 or so football games – making more than 1 million dollars per game.

Parents, similarly, caught up in the last generation’s path to success, still encourage their children to be doctors, lawyers, or management consultants. But if you can ease people’s boredom in any way imaginable, you make bank in our society. Top video game streamers – these are guys who live stream themselves playing video games – make several million dollars a year. A figure that is climbing with each passing month and will, inevitably, top out in the Romo or Lebron territory.

Musicians, actors, reality TV stars, Instagram Influencers, athletes, showrunners, news anchors, radio hosts – if you can entertain people – you are a .1%er in our society. Moderately successful entertainers and athletes in our country make far more money than top neurosurgeons, computer engineers, architects, university professors or state governors.

If price is an information signal, the earnings of those who entertain us are sending a clear and compelling message about what we value. Seventy years ago, the average professional athlete made good money. Today, they are fabulously wealthy, not just in total dollar terms but in comparison to any other job category.

Babe Ruth – probably the most dominant athlete of all time playing in the most important sport of his day – earned roughly the equivalent of a million dollars a year in today’s money. Darn good. But that’s about 40% of the minimum salary for an NBA veteran. In other words, the 10th best player on an NBA team today earns more (in adjusted dollars) than the most dominant athlete in history did a century ago.

Even in technology, where truly vast fortunes have been made, the people making those fortunes are doing it by distracting us from boredom. Thirty years ago, companies making huge money (e.g., Oracle and Microsoft) were building business productivity tools. No more. Market leading companies these days make devices or services that distract us and give us something to do.

Naturally, this causes a lot of angst. We worry that our children (us too, for that matter) are addicted to iPhones. That we are forgetting how to spell, how to write, and maybe even how to think. This may be an overreaction. Are the hours spent on Instagram or TikTok that much different or worse than a childhood (like mine) spent with Gilligan’s Island and F-Troop? And is chasing fame on Twitter different or worse than going to law school to be a class-action lawyer? Hard to say.

But what does seem clear is that we are putting an ever-greater value on being entertained and distracted. If we think of boredom as “having nothing to do”, it seems an almost impossible problem in our society. There are always things to do and, in our society, they are almost always interesting. Nobody has to shovel shit all day.

On the other hand, aspects of our culture do make boredom more likely. Amidst plenty, the amount of leisure time we have to fill has steadily increased. People don’t need to work nearly as much as they once did and there are far fewer hours to be invested in the type of household maintenance and chores that once occupied so much of our non-work hours. People have fewer children and they have them much later. They aren’t even as likely to be in a relationship. Whatever you think about the benefits of these things (nobody really wants more housework, right?), they all add up to a lot more non-dedicated time.

When you’re spending all your time on things you must do, there isn’t need or opportunity for reflection. People used to have to do this, but it’s also a choice – a way to get through living without ever having to think about life. So, even though there is no material necessity, doing nothing but work is a way for a lot of people to get by. For people less willing or able to do nothing but grind, there is time aplenty; ironically, giving people the opportunity to realize how valueless everything seems.

How could it not seem empty? Our culture provides people with no way to think about what a good life is, no useful concept of ethics or value, and no way to attach meaning to what we are doing. Spend any time away from work, and the endless opportunities for distraction begin to pall.

If the value of doing things plunges, nothing seems worth the effort of doing. That, of course, is the characteristic attitude of boredom.

That ties in with the theory Saul Bellow advances in Humboldt’s Gift. Boredom, says Bellow, is a kind of pain we experience when we don’t use our abilities. And, of course, as Bellow sees it, we are largely sleeping through our lives. Lulled by plenty into a spiritual sleep for which boredom is, like pain for the body, the spirit’s warning to the soul.

If Bellow is right and boredom is the pain that comes from unused abilities, we suffer from it because satisfying preferences doesn’t command enough of our attention and our abilities. We live under the mistaken and irrational belief that satisfying preferences is all there is. And while we will never run out of preferences to satisfy, boredom may reduce the marginal value of satisfying any of them to almost zero.

That means the pain of boredom isn’t the problem. It’s the beginning of an answer. The pain that spurs us toward a solution. In The Republic, Plato thought the erotic urge was the thing that most often jolted people out of their comfortable rut and engaged them, usually ephemerally or mistakenly, in a search for deeper meaning. Perhaps, but in our culture, the erotic, like almost everything else, has been denuded of passion. Which leaves only boredom to rescue us. That boredom is not telling us to travel more, work longer hours, or be more like an Instagram influencer. Real boredom, thankfully, cannot be cured so easily. For it is telling us that the endless satisfaction of preferences is not, and cannot be, a rational way to live.