“The young man visiting the archeological site on Skraeling Island is the same fellow who at the end of the book encounters a stranger on the road to Port Famine, but also not.”

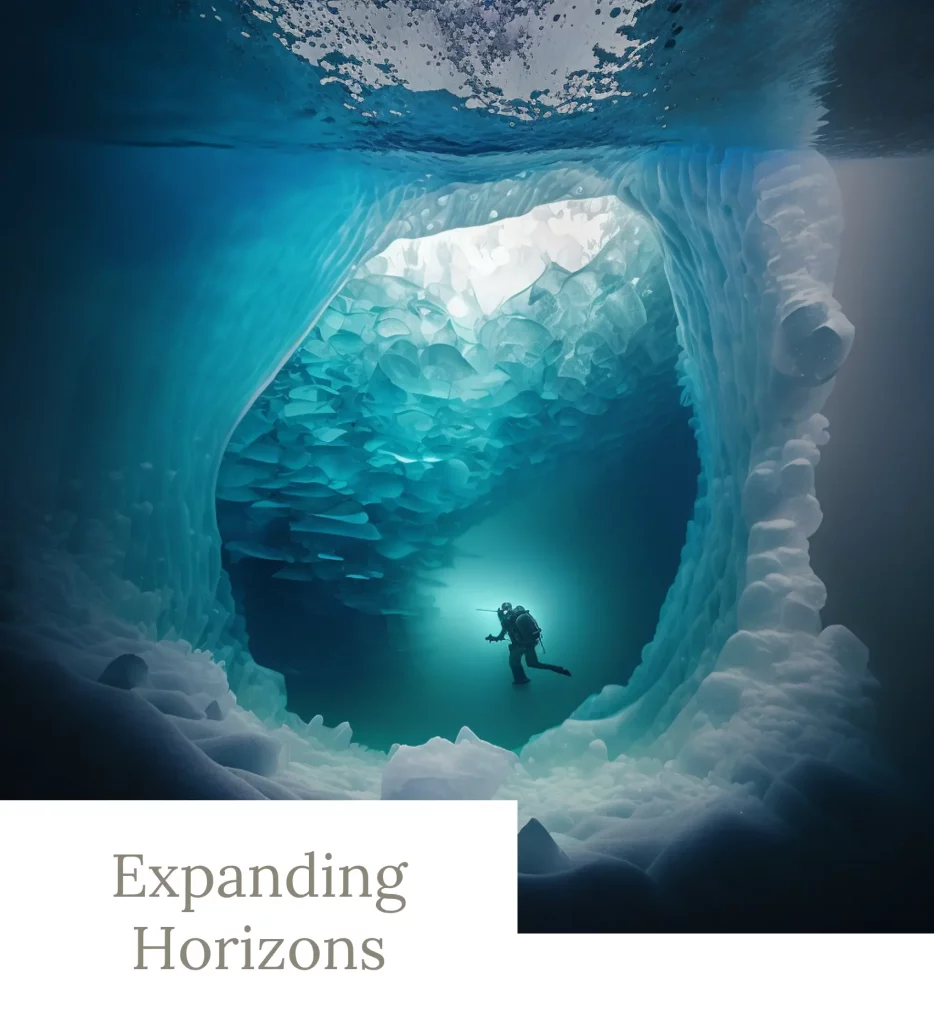

So says the end of the beginning of Horizon, Barry Lopez’s unique travelogue through a lifetime. And what a life he’s lived. It could also serve as a summation of the central theme of TW2BR – the role of transformative experience in building a life. Almost any of the chapters in Horizon (drawn from his past travels) would represent, for most of us, by far the most unusual and interesting experience of our life. Helicoptering to Thule ruins in Skraeling. Snow machining to the place where Cherry-Garrard over-wintered during The Worst Journey in the World, dry-suit diving under icebergs, meteorite collecting in Antarctica, or collecting Australopithecine fossils with a Leakey team in Africa. It’s amazing stuff, and reading Horizon often feels like you’re having a beer with Indiana Jones or the Dos Equis’ “Most Interesting Man in the World.”

It would be easy to be overwhelmed by the sheer coolness of what Lopez has done. But that would miss the point. All experience is transformative. And while big experiences tend to be more transformative than everyday ones, they carry risks as well as rewards. Every kind of life has ethical risks, and it is easy to see that living one’s whole life as a tourist might not be ideal. Part of what makes Lopez’s adventures compelling is the way he often embeds himself in real work in these exotic places. This comes through best in the later chapters of the book, especially in the Antarctic. When Lopez is collecting meteorites or dry-suit diving, it feels less like an exercise in eco-journalism and more like a glimpse into a world of extreme research that is both fascinating and intellectually appealing.

In our world, the life of constant exploration that Lopez craved isn’t readily available. It’s not a life you can buy off the rack. He had to work to create it, and like all such lives, it’s an experiment that adds value to our culture just by increasing our understanding of what’s possible. Interesting lives are inherently risky lives. The paths less traveled are often empty for a reason. Nor is it as easy to find exemplars on an empty road.

And since Horizon is a kind of summa travelogica, it’s fair to ask if the life it describes was a successful one and if the person it reveals is one we admire. In many respects, the answer is overwhelmingly “yes”. Not only has his life been fascinating, but the experiences he’s brought back and the knowledge he’s shared from his experiences are a more than generous gift to the rest of us.

Like most obsessives (and Lopez is surely a wandering obsessive), he tends toward the extreme. And for an obsessive traveler, there is nothing more extreme than the poles. His aesthetic, too, seems drawn to the empty, the cold, and the pure. He writes far more persuasively about Antarctica than about Africa or strip-mined Australia. When it comes to frozen lands, he writes very well indeed:

“What we saw when we got there had the same two effects, it seemed, on each of us. No one in the group was talking as we approached, but in that moment we all came to a standstill and remained in utter silence, motionless for many minutes. Each person finally sat down on the snow apart from the others. In a kind of vast amphitheater on the sea ice below us was the sort of wildlife spectacle one fantasizes about seeing one day, and then gazes at in disbelief, as though confronted by an illusion, a scene that would resolve itself into ordinary reality when the spell broke.

The spell never broke.

…The frozen sea is all gray and white –the gray of the fog, of smoke, the whites of gypsum. The “alleluia plain” of sunlit sea ice here carries heterogeneous patches and narrow lines of dark charcoal, with dabs of light brown within the dark patches. With my binoculars, the dollops of brown resolve into fuzzy emperor penguin young, the charcoal patches and lines into adults. The orange blotches at the back of the adults heads and the yellowish glow of their upper chest sharpen in the glass of the binoculars.

Useless, really, trying to count them. Hundreds stand on the sea ice amid the icebergs. The silence that had overcome us was only our bated breath; the air here virtually hums with the clatter and blare of the penguins’ voices, their nasal cries.

…The hour we spend with them is intimacy without narration, an experience without increments of measured time. The unvoiced emotions we felt…include inexplicable tenderness, moments of soaring elation.”

Later, he is dry suit diving in water that is literally below freezing (28.6):

“After an hour down here, most of us are ready to surface and warm up. On this day, however, with the day’s work done, I wanted to linger. Stretched out horizontally on my back in the currentless water, forty feet below the dive hole, I started to roll over slowly, like an idling dolphin. My eyes traveled first across the underside of the sea ice cover above me, with its dark communities of epontic (ice-associated) algae, until they reached the distant edge of the ice cover, meeting the dark water there and then the field of black cobbles below me. The cobble plain sloped away into the depths of an unlit ocean. My eyes roamed the potholes and undulations of the cobble plain, where massive red starfish, pale green urchins, and a kind of large, long-legged sea spider …moved with nearly imperceptible slowness…At the end of this rolling, I see the walls of the iceberg rising, and then I am looking straight up through the roughly round, six-foot-wide lens of still water in the dive hole. Through it I can see a cobalt blue sky and the dark-clad bodies of the other divers in their dry suits, their faces glowing in the sunlight reflecting off the sea ice.”

These are worlds to which most of us have never traveled and can barely imagine. Horizon has many such breathtaking visions, and it is a joy to experience them even second-hand. Basking in a sunbaked depression in the arctic ice. Twisting in the lazy circles of the suspended diver, looking up at glacier ice from below. Surveying an icy Colosseum of emperors. Lopez takes you there and gives you not just sense of place, but reason to care.

But if Horizon works very well to bring you there, it does less to get you inside Barry Lopez. If the Barry Lopez who begins on Skraeling is different from the Lopez driving in Punta Arenas at the end, the difference is a subtle one and the reader will have to find it in the time-blurred nature of his reactions. One gets the sense that Lopez does not like to insert too much of his inner geography into the story, and he rarely dips into the fully autobiographical.

“Maps held me in thrall when I was young. They combined, in a single two-dimensional space, both the broad all-encompassing reality that a great journey makes possible and the particularity of those places along the way that comprise the journey. To behold the map is to imagine, in the same instant, both the arc of the journey and the moments that will make it up.”

It’s a beautiful evocation of the power of the map to inflame and ground the journey in the mind of many a youth.

Yet Lopez doesn’t tarry here. Regrettably, he veers off into the world of adult reflection: ”This, to make a bit of leap, is part of the genius for me behind Monet’s impressionistic representations of Giverny. The unfocused colors of these sketch-like images mimic the sketchiness of one’s general recollection of movement through a particular geography.”

I would rather have heard more about the boy and his love of maps.

Is Lopez funny? Kind? Warm? Extroverted? Witty? It’s hard to say. Horizon is not expressly about a life, and it gives one less of the man than perhaps the reader will wish. The picture that does emerge is of a very competent man, earnest, thoughtful, skilled at what he does, and a little lacking in humor. Perhaps that last part is just the affect of age and the creeping bitterness that often seems to seep around the edges of Horizon and more than once swamps it. For there is too much bitterness in Horizon to swallow without remark.

If, as George Washington tells Miranda’s young Hamilton, “Dying is easy young man, living is harder”, it’s all too true that in our times, bitterness is easy, hope is harder. More than once in Horizon, Lopez lets us down, substitutes politics for life, and ideology for wisdom. What a terrible pass we have to come to when a conversation with the most interesting man alive degenerates into the sour political cant of a newly minted Vassar grad.

Lopez really should know better. The secret to change is to make people care, and Lopez can do that very well. No nag, no scold, no puritan every changed a heart or a mind. Nor is Lopez interesting when he dips into the ideological well. If spinning under sea ice is a view we’ve never witnessed, shallow reflections on capitalism, nationalism, strip-mining, clear-cutting, Apartheid and prison camps are roads we’ve all travelled many times and to which Lopez adds very little that is new or interesting. Few good minds survive the transition into the realm of politics and ideology. Lopez is not one of the fortunate.

Once or twice, he becomes almost a caricature of the guilt-ridden modern progressive. I do not know what to make of this bizarre scene from Skraeling Island where alone in a stone hut he seeks to apologize for our sins to the ghosts of a people long past:

“I stood up in the middle of the karigi and spoke quietly to the stone benches. I said where I was from, what my culture values, and I recalled some of the worthy things my culture had done. Just a few sentences. I said I admired them, admired their success, and that this music I was about to play was what someone in our culture had created, and that for almost two hundred years my own people had considered it one of our greatest works of art.

I set the small tape player upright on the stone floor and pushed PLAY. The tinny, dimensionless sound unfurled in the cool air. I imagined in that moment that the sod houses around me were a herd of bison, turning in for the night on a grassy common. But with the robust first chords of the First Movement, I began to sense my mistake. What I was doing seemed suddenly so incredibly ignorant that the brilliance of the music couldn’t suppress a sense of humiliation that began to rise in me….

I turned the tape player off and stood there on the flagstone floor facing the empty benches for a few moments. I put the machine in my pocket. Nothing to be said, really. I desperately wanted to find words that would reestablish some common ground with the Thule ghosts. Instead, I apologized for my intrusion, thanked the audience I imagined sitting there for their tolerance, and retreated….

I recalled how often I had resisted the impulse to share those aspects of my own culture that I admired…with members of a culture that had experienced the brutal force of colonial intrusion. I knew the only right gift to offer people in these situations is to listen, to be attentive.”

This is not wise in any respect.

Yet I cannot help but think that Horizon is the work of very wise man. Nor do I think there is any contradiction. We tend, with all such dispositional attributions, to overstate both their consistency and their universality. The smartest person isn’t smart at everything. Even a wise man is occasionally a fool. For a politician or a political philosopher to be a fool about politics is very bad. For everyone else, it matters very little. The important thing to know about Elon Musk isn’t his political opinions and the same is surely true of Barry Lopez.

Elide, if you will, over any moments where Horizon descends into reflections on the modern world or wallows in this kind of hair-shirt puritanism. You will miss nothing. What will remain (and a very great deal will remain) will remind you that the world can be extraordinarily interesting when seen through the eyes of an interesting man. There is much that is fascinating. Much that illuminates the essence of a well-chosen, thoughtful exploration of life. And much that is truly wise.

The themes that matter most to our lives and world run through Horizon like a powerful current. The search for a life beyond the safety of adequate remuneration. A powerful desire for community – ironic perhaps in a born traveler – but Lopez is no different than the rest of us in this regard; no matter how stable we are in place, finding community in our world is hard. A bracing, engagement with the world we traverse and a keen and never-sated curiosity to understand how it works and to value and appreciate what is good.

Horizon will remind you, too, of one of the undeniable virtues of modern culture – it allows for many, many kinds of lives. Far too few of those lives are interesting. Almost none are as interesting as the life chronicled in Horizon. Lopez has spent his life chasing far horizons. He’s a true outlier who has never accepted the walls that fasten most of us to a place and bind us to a way of life. In his own words, “when a boundary . . . becomes instead a beckoning horizon, then a world one has never known becomes an integral part of one’s new universe. Memory and imagination come into play. The unknown future calls out to the present and to the remembered past, and in that moment of expansion, the imagined future seems attainable.”

A need to travel and explore is neither good nor bad, and one could craft a great life or fall into a terrible one based on such a need. Lopez built a life for himself that meets that need; a life that stands out of the ordinary. It’s a life that has enriched our culture with its words, and perhaps even more, by its example.

It shows what may be done by someone with the courage to build the life they choose. And like all such choices, though made for the most personal of reasons, it is a gift to us all.